Will Lowering Interest Rates Really Improve the Economy?

Will Lowering Interest Rates Really Improve the Economy?

Trade Hermit - Macro Eco

Introduction: Conventional wisdom holds that cutting interest rates can stimulate economic growth by encouraging borrowing and spending. However, today’s global economic paradigm has shifted in fundamental ways, casting doubt on whether rate cuts alone can deliver the desired boost. In the current environment, treating interest rate reductions as a cure-all for economic woes is questionable at best. This report examines why a simple rate cut (even a drastic one of 1.5 percentage points, as some officials have advocated) may not materially improve the economy, given several structural changes and constraints now in play.

A New Economic Paradigm: Five Structural Shifts

Multiple long-term changes in the global landscape suggest we are in a qualitatively different economic era. These structural shifts include:

1. Deglobalization: The era of ever-expanding globalization has ended; indeed, the world has entered an early stage of deglobalization. Global trade and capital flows have slowed or even reversed in some areas. A telling sign was TSMC founder Morris Chang’s 2022 remark that “globalization is almost dead and free trade is almost dead”. International supply chains are being reconfigured, trade barriers are rising, and the easy gains from globalization are gone. This retreat of globalization undermines a key engine of past growth and cannot be fixed by monetary policy.

2. Strains in Developed Financial Systems: Developed countries’ bond markets and monetary systems are under unprecedented strain. After decades of low rates, record debt levels and recent inflation surges have pushed these systems toward crisis. The credibility of major reserve currencies and government bonds has been dented by heavy borrowing and quantitative easing. This is an irreversible break from the past environment of abundant liquidity and low yields, and it limits central banks’ room to maneuver. Lowering interest rates now carries risks – for example, excessive easing could further undermine confidence in the U.S. dollar and Treasuries, which are already facing skepticism.

3. Heightened Geopolitical Risk: Geopolitical tensions have spiked, raising the risk of conflict and a reshuffling of the global order. From the war in Ukraine to strategic rivalry between great powers, the world’s risk landscape has darkened. The “geopolitical risk coefficient” is far higher today than in past decades, meaning businesses and consumers are more cautious. Investors flock to safe havens (gold prices have jumped ~40% since late 2023, reaching record highs above $3,000/oz by March 2025) amid uncertainty. Interest rate cuts cannot resolve security fears or international conflicts – these external factors can dampen investment and trade regardless of monetary policy.

4. Technological Disruption (AI Revolution): Rapid advances in artificial intelligence are creating transformative disruptions to labor markets, education, and employment. AI’s rise is a double-edged sword: while it promises productivity gains, it also threatens to automate many jobs and displace workers on a large scale. Goldman Sachs economists estimate that generative AI could expose the equivalent of 300 million full-time jobs to automation globally. Such a revolution may upend traditional job security and wage growth, creating structural unemployment or the need for massive retraining. These profound shifts in the economic fabric are qualitative issues – simply cutting rates won’t retrain workers or reinvent education systems to adapt to AI.

5. Rise of Populist and Far-Right Governments: Across the globe, there has been a surge in populist, nationalist, or far-right governments coming to power. These regimes often prioritize short-term political gains or nationalist policies (trade protectionism, immigration restriction, etc.) that can fragment global cooperation. They also sometimes erode institutional checks and balances (e.g. central bank independence). Policy uncertainty increases under such governments. Not only do these political shifts often exacerbate the deglobalization trend, they also can lead to unorthodox economic policies that undermine investor confidence. No interest rate tweak can address the underlying social discontent or inequality that often fuels populism – those require political and fiscal solutions.

Each of these structural changes represents a qualitative transformation in the economic environment. No single interest rate cut, a quantitative adjustment, can reverse or “solve” any of these issues. In other words, the world economy has undergone a paradigm shift in which traditional monetary stimulus is not as potent as it used to be.

Why Rate Cuts May No Longer Work: The Transmission Breakdown

Monetary policy affects the economy through a long and complex chain of cause and effect. When central banks cut rates, the intended transmission mechanism is roughly as follows:

1. Cheaper Credit: Lower interest rates reduce borrowing costs. This ideally encourages one or more sectors – businesses, households, or governments – to take on more debt (leverage up), since credit is now cheaper.

2. Higher Spending and Investment: If at least one major sector increases borrowing, the extra funds are spent or invested, boosting aggregate demand. For example, households might buy more homes or cars; firms might expand factories or upgrade equipment; governments might invest in infrastructure. This step is crucial – without an uptick in borrowing and spending, a rate cut does little.

3. Production and Hiring Response: As demand rises, businesses should respond by increasing production. They may scale up capacity – building new facilities, purchasing more machinery – and crucially, hire more workers to meet the demand.

4. Improved Employment and Income: With rising employment, the labor market strengthens. Job gains lead to improved incomes and consumer confidence. More people earning wages means higher disposable income, which further feeds into consumption.

5. Positive Feedback Loop: Finally, higher consumption from better incomes fuels further demand growth, and the cycle continues in a virtuous circle of economic expansion. In theory, this completes the positive feedback loop initiated by the rate cut, resulting in broadly stronger GDP growth.

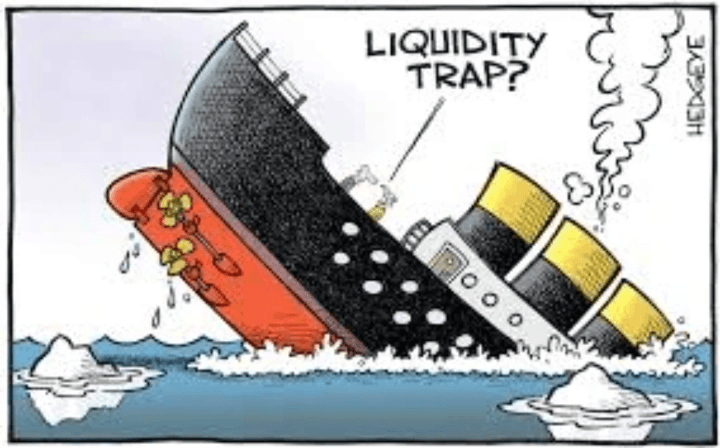

This ideal chain is long and fragile. If any link in the chain fails, the effectiveness of monetary easing is greatly diminished. For example, if businesses do not see profitable opportunities and thus refuse to borrow and invest, the extra liquidity from rate cuts will sit idle (“pushing on a string”). If consumers, burdened by debt or pessimistic about the future, do not increase spending, firms won’t hire or expand. The weakest link will determine the outcome – a phenomenon famously known as a “liquidity trap.” In a liquidity trap, interest rates can fall (even to zero) but borrowing and spending do not respond because confidence or incentives are too low.

Unfortunately, many indications suggest that today’s economy is prone to such a trap. Let us examine the potential breakpoints in the chain, one sector at a time, to see why rate cuts now may not stimulate much real activity.

Household Leverage: Consumers Are Cautious

On the household/consumer side, lower interest rates are supposed to spur big-ticket purchases like homes and cars (since mortgages and auto loans become more affordable). However, evidence shows consumers are reluctant or unable to take on more debt in the current climate:

• Housing Market Slump: Despite some easing in mortgage rates in anticipation of Fed cuts, the U.S. housing market remains cool. New home sales have been sluggish – for July 2025, sales fell 0.6% from June, and were down 8.2% year-over-year. The annualized sales rate in mid-2025 was at its lowest since late 2024. If Americans truly expected home prices to surge once rates fall, one would expect a rush of buyers trying to “get in” before the rebound. Instead, buyers are holding back, and data shows the housing sector is soft:

• Declining Prices and High Inventory: Median new house prices in July 2025 were down 5.9% from a year earlier. Unsold housing inventory remains extremely elevated – nearly 500,000 new homes were on the market, a supply level not seen since October 2007. In fact, the inventory of completed new homes for sale hit a 16-year high in mid-2025. Such a glut suggests that even recent rate relief has not enticed enough buyers; builders are cutting prices to attract demand. Homes now take over 9 months on average to sell at the current pace, indicating very slow turnover. With excess supply and fears of a housing “bubble”, many potential buyers are either unable or unwilling to leverage up for a home purchase.

• Surge in Canceled Home Purchases: Not only are fewer people buying homes, but many who did sign contracts are now canceling. Roughly 58,000 U.S. home-purchase agreements fell through in July 2025 – about 15.3% of all homes under contract that month – the highest cancellation rate for any July on record. This spike in cancellations reflects buyer hesitation due to high prices, high borrowing costs, and economic uncertainty. When would-be homeowners are walking away from deals at record rates, it’s a sign that cheaper mortgages alone won’t suddenly revive housing; underlying affordability and confidence issues are at play.

• Broader Weakness (Existing Homes and Permits): Measures of existing home prices tell a similar story: the Case-Shiller 20-City Home Price Index has recorded several consecutive monthly declines in 2025, and the supply of homes (both new and existing) is plentiful. Building permits – a forward-looking indicator of construction – have been tepid. In July, single-family housing permits barely rose (after previous declines), indicating that developers are wary of launching new projects. This wariness likely stems from two factors: (a) weak demand (developers fear homes won’t sell at good prices amid cautious consumers), or (b) high costs eating into profitability (materials, labor, and financing costs remain elevated, discouraging new builds). In either case, it demonstrates that lower interest rates alone are not enough to propel the housing sector when other headwinds (low consumer appetite or high inflation) persist.

• Auto Sales and Durable Goods: Similar caution is evident in other consumer durables like automobiles. Car sales have not shown a dramatic resurgence despite some financing deals. In fact, history suggests that during economic slowdowns, cheap credit may not overcome recessionary pressures. For example, in the 2001 recession the Fed slashed rates from 6.5% to 1.75%, enabling 0% auto loan promotions – yet auto sales still ended up roughly flat. This illustrates that if consumers are worried about jobs or already over-indebted, they may not borrow even at low rates. In the current environment, with real incomes under pressure from inflation and confidence shaky, a modest rate cut is unlikely to spur a buying spree for cars or appliances.

In short, American households show few signs of levering up in response to lower rates when their balance sheets and expectations are strained. Whether due to fears of a housing correction (a “bubble” popping) or simply tighter budgets (high inflation in essentials squeezing disposable income), consumers are not behaving as the classic textbook says – they are not rushing to borrow and spend. Thus, the first link (household leverage) in the stimulus chain is weak.

Corporate Leverage: An Uneven Playing Field

What about business investment? In theory, cheaper credit should incentivize companies – especially smaller firms or those on the margin – to borrow for expansion, since projects that weren’t profitable at higher rates might become viable at lower financing costs. However, the U.S. corporate landscape in 2025 is highly unequal, and that undermines the transmission of rate cuts:

• Profit Concentration in Mega-Caps: The U.S. stock market’s gains and profit growth have been overwhelmingly driven by a handful of giant companies. If we exclude the top seven tech “Magnificent Seven” firms, the earnings of the remaining 493 companies in the S&P 500 (“S&P 493”) have been nearly stagnant. In Q2 2025, for instance, the Magnificent 7 saw earnings soar ~26% year-on-year, while the entire rest of the index had essentially 0% earnings growth (flat year-on-year). In other words, almost all the profit growth and optimism in the market is concentrated in the largest monopolistic firms, whereas the typical firm is treading water. Inflation has been running around 3–4%, and 10-year Treasury yields are near 4%, so “flat” earnings mean the average company’s profits are shrinking in real terms and underperforming risk-free bonds. This dynamic points to a troubling trend of quasi-monopoly: a few big winners and a long tail of struggling smaller businesses.

• Reluctance to Invest: Given the above, it’s unrealistic to expect a broad swath of companies to immediately increase capital expenditures if interest rates fall. Unless firms anticipate a significant rise in future profits, they won’t take on more debt. Currently, many mid-size and small companies see limited profit margins and intense competition from dominant players. Indeed, there have been reports of smaller U.S. businesses shedding assets and scaling back, rather than gearing up, even as of early 2025. For example, some firms have been selling off prime real estate (like logistics centers) at discounts, indicating a need for cash or a lack of confidence in expansion payoffs. This isn’t the posture of a corporate sector eager to borrow and build – it’s the posture of consolidation and retrenchment.

• Credit Conditions vs. Demand Outlook: We must remember that credit is a derived demand – companies borrow if they have reason to expand production. If final demand is expected to be weak, no rational business will borrow simply because loans are cheaper. Right now, many businesses cite softening consumer spending, rising labor costs, and uncertainty about trade/geopolitics as reasons to be cautious. A small cut in the Fed funds rate will not allay those concerns. In effect, the second link (business leverage) in the chain fails if businesses don’t see profitable opportunities. And currently, outside of a few tech sectors (e.g. AI-related investments), the appetite for aggressive expansion is limited.

Thus, American businesses – especially smaller enterprises – are not poised to leverage up just because the Fed trims rates by a point or two. The benefit of cheaper credit is outweighed by structural challenges: market concentration (which stifles the competitiveness of smaller players) and an uncertain demand outlook. Rather than spurring “animal spirits,” a rate cut might simply ease financing costs for the dominant firms (which hardly need it, as they are already flush with cash), while doing little to change the behavior of the rest.

Government Leverage: Limited by Inflation and Credibility

In past crises (such as the 2000 dot-com bust and the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis), the U.S. government stepped in as the borrower and spender of last resort. The Federal Reserve slashed rates and launched quantitative easing, while fiscal authorities ran large deficits. This government leveraging – effectively “printing” money and expanding public debt – propped up asset markets and restored growth. Crucially, those interventions succeeded in part because the rest of the world still had confidence in the U.S. dollar and Treasury bonds. The global economy was still largely cooperative (globalization in full swing), so America could “sacrifice” the value of the dollar (and issue more Treasuries) to save its stock and housing markets without long-term damage to the dollar’s reserve status. In 2000 and 2008, U.S. policymakers could flood the system with liquidity knowing that the credibility of U.S. currency and debt remained intact.

Today’s situation is starkly different. If a serious downturn hits, relying on government leverage (ultra-loose monetary policy and heavy deficits) is much riskier because the usual rescue tools themselves are under question:

• Dollar & Treasury Under Strain: Unlike in earlier episodes, now U.S. financial assets themselves exhibit bubble-like features and eroding trust. After successive rounds of quantitative easing and mounting federal debt (U.S. debt-to-GDP is at multi-decade highs), investors are wary. Inflation, while off its peak, has been persistent enough to erode the sanctity of “safe” government bonds. We see this in market signals: for instance, gold prices hitting all-time highs reflects hedging against a loss of faith in fiat money. If the economy falters and the Fed responds by aggressively cutting rates and re-expanding its balance sheet, there is a genuine risk of undermining the U.S. dollar’s credibility. Essentially, using the “printing press” recklessly now could call into question the very basis of the financial system – just as the excessive money printing of the late 1960s led to the collapse of the Bretton Woods gold standard in 1971, followed by a decade of stagflation. The historical analogy is apt: back then, the U.S. overissued dollars (relative to gold), breaking trust and causing a monetary regime shift; today, overissuing dollars relative to economic output could similarly break confidence, leading to a loss of reserve currency status or unanchored inflation expectations.

• All Bubbles At Once: Previously, U.S. policymakers could choose to “sacrifice” one asset to save another – e.g. let the dollar weaken to support Wall Street and housing. Now, however, multiple asset classes appear overvalued concurrently: equities (especially certain tech stocks), real estate, and bonds. If a recession hits, there’s no obvious sacrificial pawn that can be taken to protect the king. Using fiscal and monetary firepower to bail out stocks or property now directly risks inflating the debt bubble or vice versa. It’s a far more delicate high-wire act.

• Globalization’s Unwind – Less Willing Foreign Financing: In the early 2000s and again post-2008, global capital (from China, Gulf states, Europe, etc.) was eager to buy U.S. Treasuries and dollars, financing U.S. deficits. That was the era of the “global savings glut.” In a deglobalizing world, foreign appetite for U.S. debt is no longer assured. If the U.S. government tries to lean on debt-fueled stimulus now, it might find fewer takers for its bonds unless yields rise (which would counteract the rate cuts). In essence, the U.S. cannot as easily externalize its problems by borrowing from the rest of the world – not when trade and diplomatic relations are fraying.

Given these constraints, the government leverage option is much weaker than before. Even though in principle the U.S. Treasury or Federal Reserve could step in with massive easing, they are likely hesitant (rightly so) because the “rescue medicine” may poison the patient this time. Evidence of this hesitancy is apparent: despite political pressure, central bankers worry that cutting rates too fast could reignite inflation or asset bubbles. Investors, for their part, are already pricing in the risk – e.g. yields on longer-term Treasuries haven’t fallen drastically at the mere hint of rate cuts; and gold’s strength underscores lingering inflation fears if policy gets too loose.

The Liquidity Trap and Diminishing Returns of Easing

Bringing together the above points: households aren’t biting, businesses are cautious, and government hands are tied. This is the recipe for a classic liquidity trap, where monetary policy loses traction. We may pump liquidity into the system, but it ends up sitting idle in bank reserves or flowing into financial speculation (e.g. stock buybacks by cash-rich monopolies) rather than productive investment. In such a scenario, no amount of rate cutting will jump-start broad economic activity – instead, we get pushing on a string, or worse, perverse effects like asset bubbles alongside economic stagnation (stagflation).

Japan’s experience over the past few decades is instructive: rates have been near zero for years with little impact on growth because structural issues (demographics, productivity, debt overhang) muted the transmission. The U.S. and global economy in 2025 faces its own structural drags as outlined. Simply put, when an economy undergoes a qualitative shift, quantitative measures have sharply diminishing returns.

More Money, But Who Gains? Risks of Misallocation

If the Federal Reserve succumbs to pressure and embarks on substantial rate cuts (or even renewed quantitative easing) in this environment, one likely outcome is misallocation of liquidity. Rather than flowing to Main Street (small businesses, average households), the easy money could accumulate in the hands of those already financially powerful:

• Monopolies Absorbing Liquidity: Large, dominant corporations – which we noted are enjoying outsized profit growth – could use cheap funding to further entrench their position. They might finance acquisitions of smaller competitors (reducing competition), pour money into stock buybacks (boosting their share prices and executive pay, but not hiring), or invest in capital-intensive tech that doesn’t create proportional jobs. The result would be widening inequality and even more concentration of market power. Essentially, if the Fed “prints” money in a structural low-demand environment, the funds risk being captured by the financial elite rather than stimulating broad activity. This is not a theoretical concern; it mirrors what happened after the 2008–09 QE programs and the 2020 pandemic stimulus to some extent – asset prices and corporate balance sheets swelled, but the wealth gap increased.

• Zombie Companies vs. Creative Destruction: Ultra-low rates can keep unproductive “zombie” companies alive by allowing them to refinance cheaply, even if their business models are failing. In an economy that arguably needs structural change (new industries to replace declining ones), this can delay necessary adjustments. For example, if an old-line firm facing secular decline can roll over debt at low rates, it may avoid collapse for a while – but it also ties up capital and labor that could be reallocated to more innovative sectors. In the long run, this hurts dynamism.

• Inflation or Currency Risks: As discussed, flooding the system with liquidity when supply-side and structural issues are binding can lead to too much money chasing too few truly productive opportunities. This is a recipe for either asset inflation (bubbles) or consumer inflation if the money somehow circulates without output keeping pace. If investors sense this imbalance, they may preemptively hedge by moving out of fiat currency – exactly what the surge in gold suggests is happening. In an extreme case, confidence in the currency’s value can waver, threatening the dollar’s global standing. The U.S. is not there yet, but the trend is worrisome enough that continued heavy easing is not a free lunch.

The Trump Factor: Policy Choices and Consequences

The current U.S. administration’s policies add another layer to the analysis. President Trump (in this scenario, in office in 2025) has pursued a mix of strategies to boost the economy and U.S. markets – tax cuts, deregulation (including relaxing oversight on big tech and other giants), tariff wars and demands that allies invest in the U.S., and even mooting the idea of leveraging digital currencies/stablecoins to reinforce dollar dominance. Almost all conceivable tools have been thrown at the economy: fiscal stimulus via tax cuts, administrative pressure on domestic and foreign investors, protectionist measures, etc.

What remains in the toolkit are essentially monetary easing and military leverage, both of which have serious limitations:

• Monetary Easing under Political Pressure: President Trump has been vocally critical of the Federal Reserve for not cutting rates sooner and deeper. His Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent, made an unprecedented call for the Fed to immediately slash rates by 150–175 basis points – a clear sign of political pressure on the central bank. This pressure has also manifested in threats to Fed independence. While Trump’s bully pulpit may force the Fed’s hand in the short term (few central bankers can withstand sustained political onslaught), it sets a dangerous precedent. If markets perceive that the Fed is capitulating to politics, confidence in the institution’s commitment to price stability could erode, which in turn undermines the effectiveness of any rate cuts (investors might demand a risk premium, causing long-term yields to fall less than short-term rates, or the currency to weaken). Moreover, should the Fed comply and cut aggressively, what if it doesn’t work? The administration will have used its last bullet. As discussed, a failure of rate cuts to spark growth would leave the economy with little else to try except even more extraordinary measures.

• “Small Government, Big Business” Dilemma: The Trump administration’s philosophy has been one of deregulation and a smaller public sector role, entrusting growth to the private sector. Combined with the tax cuts, this has meant rising budget deficits (as revenues fell) even before any new recession. Now, paradoxically, the administration wants the private sector (households and firms) to lever up, while it seeks to contain government debt. This is the opposite of what happened in 2008–09, when the government leveraged up (bailouts, stimulus) to allow the private sector to de-leverage after the crash. The current approach is inherently riskier: if households and businesses fail to or cannot take on more debt, and the government also tries to cut its own debt, the result is a contractionary impulse. On the other hand, if the private sector does take on debt now, it could become overextended quickly, since the underlying structural issues (monopolies, inequality) haven’t been solved – leaving a more fragile economy down the road. It’s a lose-lose scenario unless structural reforms accompany the strategy.

• Military/Geopolitical Gambits: External conflict or saber-rattling has historically been a way for countries to distract from or alleviate domestic economic strife (through defense spending or rally-round-the-flag effects). The Trump team has indeed taken a hard line on geopolitical rivals (China, Russia, Iran), forming an encircling strategy. However, military options are constrained. One underappreciated reason is the U.S.’s reliance on strategic imports like rare earth elements from countries like China. As an example, Western dependence on China’s rare earth minerals (essential for high-tech manufacturing and defense) acts as a circuit-breaker on aggression: “hostility is restrained by Western dependence on China’s rare earth supply chain”. In mid-2025, the U.S. even had to make concessions (e.g. easing some chip export bans) to ensure China continued supplying these critical materials. Thus, large-scale military escalation that might stimulate the economy (through wartime spending) is unlikely, and even if attempted, could backfire economically due to supply chain choke points. In sum, the external “escape valve” is largely closed off.

President Trump’s strongman tactics (pressuring Congress, the Fed, allies, etc.) may hold things together temporarily, but they do not solve fundamental problems like an unfair distribution of income and wealth, or monopolistic dominance in the economy. In fact, by rolling back regulations on big companies and cutting taxes for the wealthy, the administration arguably worsened those divides. This represents a missed opportunity: with significant political capital, the leadership could have pushed through serious internal reforms (antitrust enforcement, infrastructure investment, education/workforce retooling) to address the root causes of malaise. Instead, that political capital has been spent largely on elevating short-term market metrics and headline GDP, leaving the structural rot untouched.

The question arises: what happens after Trump? The analysis must consider that any boom engineered now via extraordinary measures could be short-lived, while the structural issues outlast the presidency. A successor without Trump’s personal influence (the text mentions a figure named “Vance” as an example) would likely find it impossible to manage an economy dominated by entrenched monopolies and burdened by even higher debt. In other words, even if aggressive rate cuts or other tricks produce a brief spurt, they may simply defer the reckoning and make it worse.

Conclusion: Structural Problems Demand Structural Solutions

Cutting interest rates is a quantitative change; today’s challenges are qualitative. The global economic paradigm shift – deglobalization, financial stress, geopolitical realignment, technological disruption, political populism – has fundamentally altered the landscape in which monetary policy operates. A broad lesson from economics is that trying to solve structural (qualitative) problems with cyclical (quantitative) tools is ineffective. It’s akin to treating a serious illness with painkillers – it might mask symptoms for a while, but it doesn’t cure the disease and can lead to dependency.

At this juncture, the effectiveness of a Fed rate cut (even a dramatic one) is likely to be muted. Households are constrained or pessimistic, businesses face an uneven playing field and uncertain demand, and the government’s usual firepower is limited by inflation and credibility concerns. If the Federal Reserve proceeds to slash rates without addressing these issues, the most probable outcome is a mild temporary uptick in financial markets but little improvement on Main Street – in other words, a liquidity trap scenario. In the worst case, such policy could even sow the seeds for a deeper crisis: fueling asset bubbles or undermining confidence in the dollar, eventually leading to stagflation or a lost decade reminiscent of the 1970s.

For a primarily American audience of financial and policy professionals, the implication is clear: monetary policy cannot carry the burden alone. It is not 2008 or 2020, when simply “more liquidity” was the obvious answer. Instead, what is needed now are structural and fiscal interventions. These might include: investment in productivity-enhancing infrastructure and education (to adapt to AI), policies to boost labor income and reduce inequality (so that consumers have the confidence and means to spend), and regulatory measures to ensure competitive markets (so that the gains from any stimulus are not siphoned off by monopolies). In addition, a realistic reassessment of globalization’s unwind is needed – ensuring resilient supply chains and trade relations without reverting to destructive protectionism.

In summary, relying on interest rate cuts as a panacea is a flawed strategy under current conditions. As painful as it may be to admit, there are no quick fixes from the central bank for what ails the economy. Structural problems require structural solutions. Until those are pursued, any monetary easing will likely have diminishing returns, and expecting a 1.5% rate cut to magically solve deep-seated issues is, to put it bluntly, wishful thinking. The risk is that by the time this becomes evident, the U.S. will have wasted valuable time (and policy ammunition) and may find itself in an even more difficult predicament – one where, indeed, even printing money no longer helps, the classic liquidity trap realized.

Ultimately, sustainable economic improvement must begin from within: fix the internal imbalances and inefficiencies first, then monetary policy can support a healthy cycle. Without that foundation, rate cuts alone are pushing on a string – a quantitative move in a world that has moved on qualitatively.